Patricia Politano

“As long as these people considered my brain useless and my facial expressions and sounds meaningless, I was doomed to remain ‘voiceless.” (Sienkiewicz-Mercer & Kaplan, 1989).

In her autobiography, “I raise my eyes to say yes”, Ruth Sienkiewicz-Mercer, a disability rights advocate, explains that despite her strong desire to communicate, her communication success depended entirely on the observation skills of others, their willingness to communicate in alternative ways, and most importantly, their expectations about her. As an infant, Ruth developed epilepsy and incurred damage to the motor cortex of her brain. She lost the ability to control her limbs and the muscles involved in speech. When her parents were no longer able to care for her, she was placed in a state institution where staff did not know her or how she communicated. In this setting, no one attempted to communicate with her. She claimed, the staff thought her yes-and-no signals were “mindless gesticulations” and she “had no way of telling them anything different”.

Unfortunately, Ruth’s experience is not entirely unique. Most people who use alternative communication methods report that others often underestimate their capabilities and don’t know how to communicate with them. The skills and knowledge of communication partners play a vital role in the success of communication interactions. This is especially true for individuals who are pre-symbolic communicators.

Pre-symbolic communication refers to communication methods which do not utilize spoken words or signs. Examples of pre-symbolic communication are common gestures, such as head nodding/shaking for yes/no and waving hello or goodbye; as well as less conventional signals produced with body movements, vocalizations, and facial expressions. These signals can be movements and gestures which are unique to an individual and may be very subtle, such as raising one’s eyes to say YES, as described by Ruth Sienkiewicz-Mercer. When individuals only have pre-symbolic methods of communication, they are limited in what they are able to express and only a few people are able to understand them. Before a child develops speech, he or she may only be understood by a sibling or a parent. Young children who live in a hospital or institutional setting, may only be understood by the direct-caregiver(s) who assist them most often. Even the most devoted caregiver(s) may not understand everything a child attempts to communicate without words. If a child lives in a setting where no one expects them to communicate, their communication attempts may go unnoticed. Further If a child’s communication signals are unique or subtle, they may be understood by fewer people and less often.

Information about normal speech development can help us understand how unique signals for communication develop. Infants communicate primarily through gestures and vocalizations before speech develops. As caregivers assign meaning to infant behaviors, infants develop an association between the vocalization/behavior and the event that follows. For example, if an infant pushes food away or spits out food during a meal, the caregiver may interpret this as a signal that the child is finished eating this food and stop the activity. Caregivers typically will model spoken word, while responding to the associated behavior. For example, a caregiver may say e. g. “no”, “all done” or “finished” while stopping the activity. Typically- developing children hear speech models paired with actions repeatedly before they learn to speak a word. As the child begins to produce speech, he discovers that speech is a more effective, and the communicative behaviors are replaced with speech and common gestures.

Children who do not develop speech also rely on primary caregivers to assign meaning to their behaviors. They may similarly learn that pushing food away during a meal is a way to communicate no, all done or finished. However, if they are unable to imitate the verbal models of “no”, “all done” or “finished”, they will continue to use pre-symbolic behaviors to express this message. The number of messages communicated though non-verbal communicative behaviors can grow to be very complex. Further, as the number of signals grow, they may become more unique and less recognizable to an unfamiliar person.

It is important to note that not all behavior is communicative. Research suggests that challenging behaviors are exhibited for one of four functions: a) to escape or avoid and undesired activity b) to gain a desired tangible object c) to gain attention or d) in response to internal or external stimulation (Walker et. al., 2018). It can be confusing when a child has behaviors that are both communicative (e.g. for tangibles, attention or escape) and non-communicative (in response to stimuli). For example, a child might hit the sides of his head in response to loud noise (external stimuli), in response to hunger (internal stimuli), or to escape an activity. In these situations, a systematic functional behavior analysis may be necessary to identify when and where behaviors are exhibited with communicative intent. For many children, teaching them an alternative way to communicate that message (e.g. desire to escape an activity) can significantly reduce behaviors that are harmful to the child or someone else (Bopp, Brown and Mirenda, 2004). Teaching a child to replace a harmful behaviors with a communication method is referred to as functional communication training (FCT). Research suggest best practice for a child with severe communication impairments and challenging behavior includes a functional behavior analysis and FCT (Tiger, Hanley and Bruzek, 2008). Best practice to improve communication for pre-symbolic communicators includes: 1) assembly of a comprehensive inventory of the individual’s communication methods and their intended meaning, 2) teaching other communication partners how to perceive and understand current communication attempts and 3) modelling and teaching alternative ways to communicate. The focus is on functional communication goals to increase the number of successful communicative interactions. Intervention should aim to increase the number of messages that can be perceived and understood by a more people in more situations.

Identifying Pre-Symbolic Communication

If a child has a repertoire of idiosyncratic or subtle communicative signals, the team will need to identify knowledgeable informant(s) who know the meaning of these signals. Interviews with the informant(s) should then be conducted to assemble and document a comprehensive inventory of the individual’s communication methods and their intended meaning. There are a variety of free checklists and interview tools for collecting and documenting all the communicative behaviors perceived by familiar communication partners.

Personal communication and language description

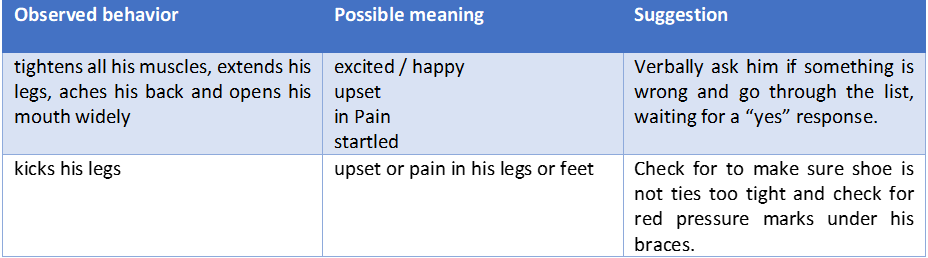

The most common tool is a personal communication and language description. Ithas at least three columns (see Figure 1). The first column contains detailed descriptions of the communicative behaviors that the child demonstrates. The more detailed the description, the more likely others will be able to recognize the behavior and the more likely others will be able to respond to that communicative behavior. In some situations, a photo may accompany the description.

The second column lists what the behavior may mean. Often one behavior will have multiple meanings. For example, when a child with cerebral palsy tightens all their muscles and extends their position, it could indicate excitement, or discomfort. Also, a child may have multiple behaviors that have the same meaning. For example, when a child does not like a specific activity, they may produce a specific vocalization that is interpreted as a protest, stiffen their body posture, turn their head away, and/or push objects away.

The final column is a description of how the caregiver responds to the child’s behavior. For example, during a meal, if a child demonstrates a behavior interpreted as a protest, the caregiver may respond by stopping the activity (taking the spoon away) and/ or modelling a head shake for “no” and saying, “Yuck, you don’t like that.”

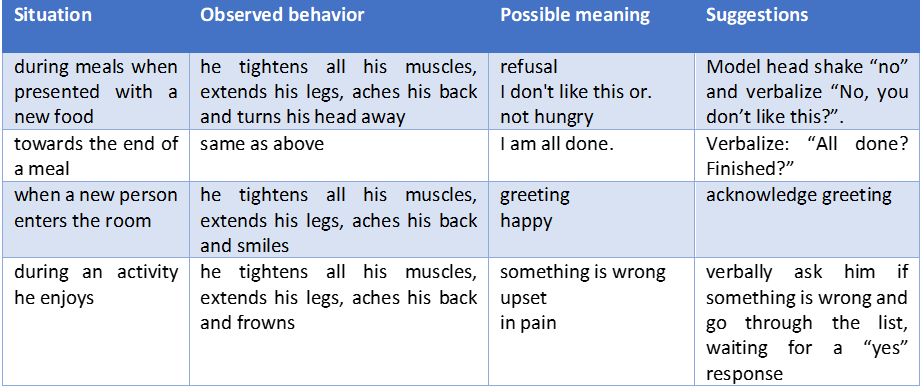

When a child has a behavior which has different meanings in different contexts, a fourth column may be added which describes the situation (see Figure 2).

Each significant person should share what they know about the child’s communicative behavior by adding items to the described tool in order to create the most comprehensive list that includes communicative attempts observed by communication partners in a variety of settings. When this information is shared, use of the list alone can be effective in increasing the number of communication partners and the number of successful communicative interactions for a pre-symbolic communicator.

Communication Checklists

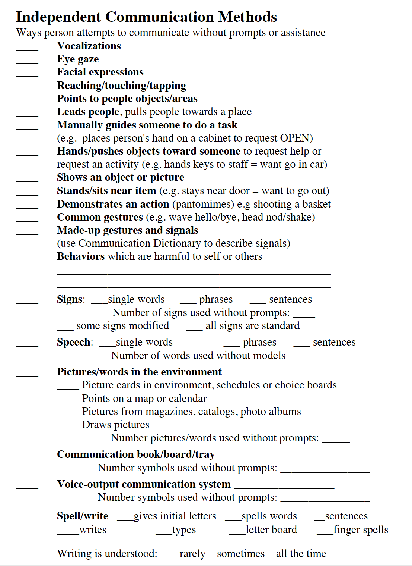

There are several other different checklists available to aid in gathering detailed information about communication methods used by an individual (Politano, 2002; Rowland, 2020; Weatherby, 1995ab), for example The Inventory of Functional Communication (abbreviated IFC) has been translated into Croatian. It is an interview guide that can be used to gather more information than the personal description of communication and language. Not all caregivers are aware of all the signals they respond to. The interview process using the IFC is designed to help caregivers recall the communicative behaviors they observe and respond to. The IFC is most effective when a service provider interviews one or more knowledgeable informants. It is possible to start with the section entitled “Independent Communication Methods” on page two. This is list of communication methods commonly utilized by individuals who cannot rely on speech for communication (see Figure 3).

With each item in this section, the interviewer would describe the communication method, give examples and deliver follow up questions to gain the maximum amount of information. The interviewer might ask, for example, “Does the child make any sounds or vocalizations?” , “ What does it mean when you hear that sound?”, “Does he use any sounds to get your attention?”, “ Does he make a certain sound when he is hungry or uncomfortable?”. Rather than just checking the item on the list, it is useful to document all the information gained. You may use the tool for describing communication and language on page three to gestures and multiple meanings where appropriate.

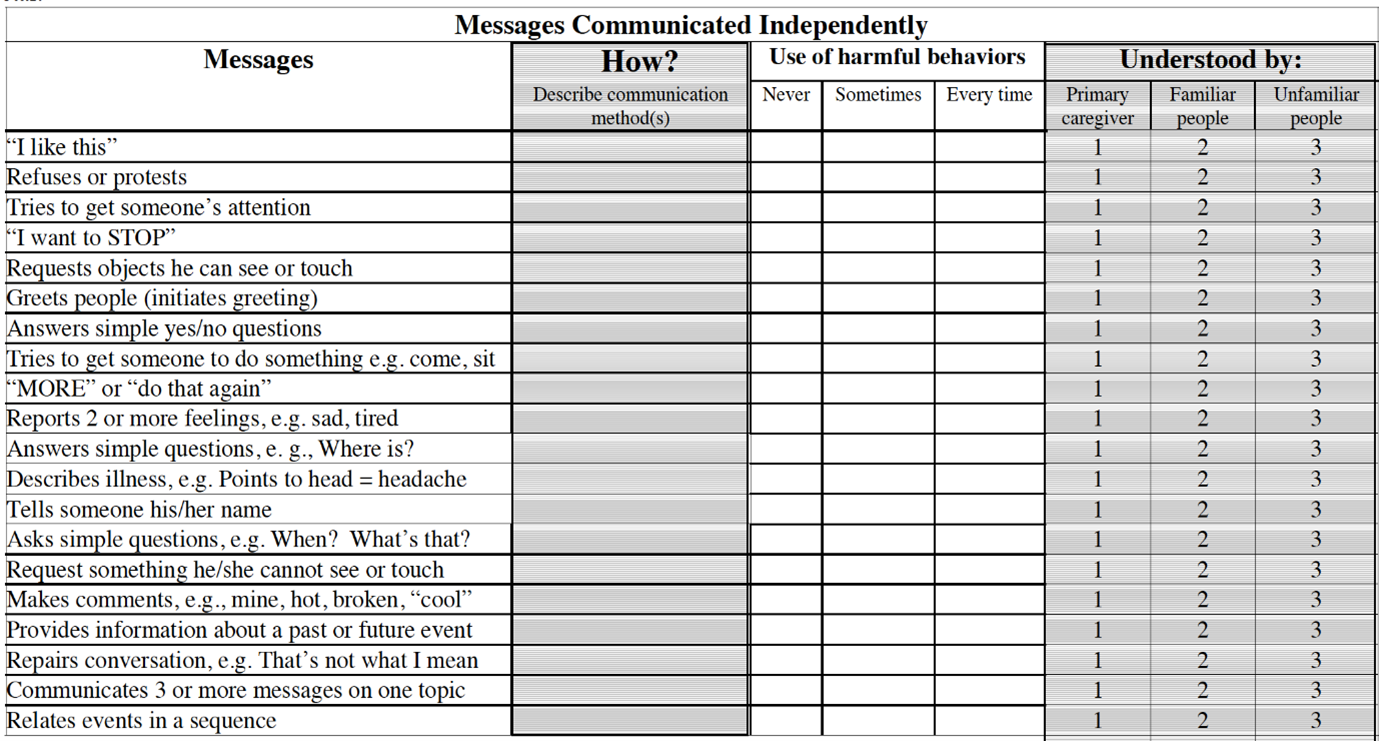

Page four of the IFC is a chart used when interviewing the caregiver about the types of messages the child is able to communicate. The first column lists communicative functions, types of messages, in developmental order (see Figure 4) The interviewer would start at the top of the list and ask, “Can you tell when he likes something?”, “How do you know he likes something?” “What does he do?”. The next column is a space for writing all the ways the child indicates likes and acceptance. The next column is for indicating if the child ever communicates this message in a way that is harmful to themselves or others.

The final three columns are used to document how easy it is for an unfamiliar person to recognize or understand this communicative behavior. For example, if a child communicates refusal in two different ways, (e.g. sometimes, by putting his head down on his desk and sometimes by throwing an item). The interviewer would list both ways in column two, mark “some of the time” and select “2” familiar people.

Personal Communication Passport

Another free tool for gathering comprehensive information about an individual’s communication is a Personal Communication Passport. The Passport is a book typically written in first person that describes more about the person. It includes how to best support the person, likes and dislikes, who and what is important to them and all the ways they communicate. The book may be created for a specific situation. Figure 5 shows a communication passport designed specifically for use in the hospital to educate staff about how a child communicates.

Templates and more information about Communication Passports can be downloaded from https://www.communicationpassports.org.uk/. Like the other tools described in this section, this aid is best created with input from familiar caregivers. It important to consider that several stages of pre-symbolic communication have been introduced in the literature, and in some stages, the child’s behavior does not have specific intent. Intent develops as the child learns the association between his/her behaviors and their effects. For this reason, training of communication partners is an integral part of intervention for pre-symbolic communicators.

Training communication partners

Research show that training communication partners is an effective method of intervention to improve communication success of pre-symbolic communicators. Partner training can be as basic as sharing information about one child’s communication methods so that partner will learn how to interpret and respond to subtle communication attempts. Training can also be focused on learning specific skills such as how to model use of alternative communication methods throughout everyday activities. Once completed, description of communication and language with four columns and/or personal communication passport should be shared with all communication partners. Teaching new communication partner how to interpret and respond to subtle and unique communication attempts increases the number of communication partners, and the number of successful communicative interactions, for pre-symbolic communicators.

To learn alternative communication methods, children need to learn the symbols that can represent the message they want to express. They need to see people repeatedly pointing to symbols while saying a word and demonstrating the associated action in order to learn the relationship between the symbol and the message. Just as speaking children learn from speech models, children who will be using alternative communication methods need to see others use symbols paired with speech. The more often they see these models, the more likely they are to develop the association. Teaching communication partners to model the use of symbols helps the child learn the meaning of symbols. Modelling use of symbols can occur during everyday activities. For example, a parent could point to a photo when offering her child choices. “Do you want milk?” (point to photo of milk) “Or do you want juice” (pointing to juice). There is no expectation that the child will point to the symbol. This type of intervention has been referred to in the literature as multi-modal communication, aided language input and aided language stimulation.

Teaching alternative communication methods

The goal is to teach the child new ways to communicate messages. These new ways should be easy for his communication partners to understand and easy for the child to produce.

Teach one new message at a time.

Children are most successful in learning new communication methods when they are motivated to communicate. Consult with primary caregivers and/or look at the messages on the description of communication and language to determine the message the child is most motivated to communicate. For some children this will be a request for a specific activity or type of stimulations (e.g. a favorite food, bouncing, rocking, music). For others it may be attention and interactions with a favorite person. While other may be most motivated to be request refusal or to control when an activity stops.

Studies also show direct teaching of alternative communication methods to be effective. One direct teaching strategy involves structuring play to elicit a request. Specifically, the teacher or therapist will: a) start a high interest activity (such as bubble blowing), b) suddenly stop the activity (when the child is very engaged in the activity), c) wait for the child to indicate the desire for more (bubbles) and d) prompt the child to communicate that message using alternative method (e.g. touch symbol for bubbles).

Prompts are faded throughout training. Initially, the therapist may manually assist the child to touch a symbol or activity-associated object. Later, delay the prompt or reduce the prompt by gently touching the child’s elbow and/or shining a light on the symbol, delay the prompt or reduce the prompt by gently touch the child’s elbow and or shining a light on the symbol.

Conclusion

Many children who are unable to communicate through speech, develop alternative ways of communicating that may only be understood or perceived by caregivers. It is important for service providers, to assume that all children communicate. Best practice for non-symbolic communicators involves working with caregivers to create a comprehensive summary of the child’s non-verbal communication methods and to share these methods with more people so that the child can have successful communicative interactions with more people in more settings. Finally, intervention plans designed to teach new communication methods should be driven by the interests of the child, based on the messages communicated using their non-verbal method.

Bibliography

Bopp, K., Brown, K., & Mirenda, P. (2004). Speech-language pathologists’ roles in the delivery of positive behavior support for individuals with developmental disabilities. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13, 5–19.

Sienkiewicz-Mercer, R., & Kaplan, S. B. (1989). I raise my eyes to say yes. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Rowland, C. (2020). Communication Matrix. https://communicationmatrix.org/

Politano, P. (2002). Inventory of Functional Communication.

Tiger, J. H., Hanley, G. P., & Bruzek, J. (2008). Functional communication training: a review and practical guide. Behavior analysis in practice, 1 (1), 16–23.

Walker, V. L., Lyon, K. J., Loman, S. L., & Sennott, S. (2018). A systematic review of Functional Communication Training (FCT) interventions involving augmentative and alternative communication in school settings. AAC: Augmentative & Alternative Communication, 34 (2), 118–129.

Weatherby, A. (1995a). Checklist of Communicative Functions and Means. Downloaded fromhttps://connectability.ca/Garage/wp-content/uploads/files/communicativeFunctionsChecklist.pdf

Weatherby, A. (1995b). How to use the Checklist of Communicative Functions and Means. Downloaded from https://connectability.ca/2011/10/19/how-to-use-the-%e2%80%9cchecklist-of-communicative-functions-and-means%e2%80%9d/